How many stories are there in the world?

Nobody knows. Some say seven, some say eight. Some say ten. I say one.

One. With two variations. One story, told over and over again, millions of times across the world.

Must be quite a story.

Basically, the story involves someone (human or otherwise) who undertakes a journey (real or metaphorical) which will change them.

That's the story. And the two variations? Does it end happily, with the promise of new life for the hero and possibly a productive relationship? Comedy. Does it end unhappily, with the death of the hero? Tragedy. But the story remains the same.

A few days ago I introduced the image of the bridge as a metaphor for the three Act structure of a script. With the addition of the Mid-Point, the bridge tells us that scripts should subdivide neatly into four more-or-less equal sections:

First quarter: Act One ('Set Up'; approaching the bridge)

Second quarter: Act Two - first part ('Story'; crossing the bridge; approaching the Mid-Point)

Third quarter: Act Two - second part ('Story' continues; crossing the bridge, away from the Mid-Point)

Fourth quarter: Act Three (climax and resolution)

This is very useful. A full-length screenplay of, say, 100 pages is a daunting prospect. But a full-length screenplay made up of four sections, 25 pages each, is easier to tackle, especially when you know exactly what needs to happen in each section.

The Road to Enlightenment is the story structure. It fits neatly over the bridge structure for the script. Or, to put it another way, with both structures in your head (the Bridge and the Road) you have a perfect working structure that will keep your story and your script on the straight and narrow.

The Road starts with an everyday world in which something is wrong. There is, or has been, some disruption to the happy continuity of everyday life. The hero feels this. He or she is aware, if only dimly, of something being not quite right.

The hero wants something. He or she is restless. There is a burning desire in there. That desire is for a better life.

Adventure calls. This is a rule of storytelling. The hero receives an invitation to go on the quest. But the hero turns it down.

Ever been going on holiday and felt at the last minute that maybe you'd rather not go? Leaving your comfort zone isn't easy, and it shouldn't be for the hero, either.

But the story must unfold. Adventure refuses to be ignored. Something happens which makes the hero take a deep breath and set out on the road.

End of Act One. The script is a quarter of the way through.

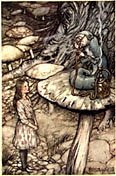

The hero is now in a new and wondrous world. Everything might look the same, but the rules have changed. In a romantic comedy, everything the hero sees is refracted through the eyes of one who is in love. In a mystery, the hero has entered the world of shadows and duplicity that is the case. The hero has to get to grips with this new world and its rules.

Like a foreign country, the world of adventure (the 'Story' - Act Two) is both exotic and threatening. The hero must discover whether the people he or she encounters are friends or foes. The unexpected can happen at any moment.

Little by little, the hero approaches the place of ordeal. The Mid-Point. The dragon's lair. Death's citadel.

The hero has an objective. Something stands in the way of that objective being achieved, the dream realised. That something lives at the Mid-Point.

And, as we all know, dragons guard treasure. Whatever the hero is searching for, the answer will be found at the Mid-Point, where Death lives. Halfway through the script, the hero faces a major challenge. Oblivion is threatened (the loss of the loved one, failure, loneliness, humiliation or an unpleasant death). Simultaneously, the hero finds the answer - the thing he or she has been searching for.

The story is about growing up, about developing as a person. The old self has to die for a new self to be born. This is acted out in initiation rituals. It is the change which happens in the midst of neurosis. The hero emerges from his/her Mid-Point encounter with Death a stronger person. He or she now has the key to the story.

The hero must escape from Death's lair. Just after the Mid-Point, there's usually a chase or a flight, as the hero, alone or with others, evades Death's clutches, putting a good deal of space between themselves and the Death Star.

The objective hasn't yet been achieved. But the hero now knows what must be done.

The hero, stronger, now, after surviving the Mid-Point encounter with Death, has to marshal his or her forces, their resources, and take the battle to Death. For this to happen, there has to be a kind of return to the beginning. We have to get out of the story world, off the bridge, back to the world we're familiar with. The hero has to leave the world of adventure behind. Living in a story is like living in a dream - it can't go on indefinitely.

Just as the hero had to be forced to set out on the road, to leave the comfort of home behind and begin the adventure, so the hero must now be forced to put the adventure behind him and get down to the serious business of resolving the story.

End of Act Two.

The final confrontation with Death happens much more on the hero's own terms. Lessons have been learnt. The hero now knows who his or her friends are. We have also spotted Death's weaknesses. Something that was stolen or appropriated at the Mid-Point will prove to be the key to the whole thing, and that can now be used. The hero will triumph.

Joseph Campbell, who first noticed that all the world's stories are essentially the same ('The Hero With a Thousand Faces'), called the last stages of the cycle - or Act Three, in our terms - 'Master of the Two Worlds' and 'Freedom to Live'.

In Act Three - the final quarter of the script - the hero demonstrates that they now have the ability to survive both the world of adventure and the everyday world of home. He or she has conquered Death. The mystery is solved. Love blossoms. The hero is free to live.

There will be a marked difference in the hero at this final stage in the story. If your protagonist remains essentially the same at the end as he or she was at the beginning, then their hero status might be lacking.

If they haven't learnt something about themselves from their close encounter with Death, then they're not really a hero.

And boy, do we need heroes.

Saturday, 11 October 2008

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

nice blog, haven't thought about "two stories" in the world in that way.

yes, we need hero's (or anti-hero's) to inspire us.

we're in a fucked up miserable time, sigh, oh god I need someone to inspire me and enlighten me. I can't wait to see Angelina Jolie in her new action film coming out (Edwina A. Salt, I think it's called).

Post a Comment